Research

One of the most important discoveries in genomics is the realization that only 1-2% of the DNA in the mammalian genome is capable of encoding proteins, while more than 90% of the genomic DNA is transcribed into non-protein-coding RNAs. Our lab uses math, bioinformatics and biology tools to decipher the complex regulatory network mediated by RNA code, which may has significant implication for human diseases diagnosis and treatment.

Current Research Direction:

Noncanonical small RNAs

- Developing novel small RNA sequencing methods and analysis tools

- Discover noncanonical small RNA species and their functions

Mammalian embryo symmetry breaking

Noncanonical small RNAs

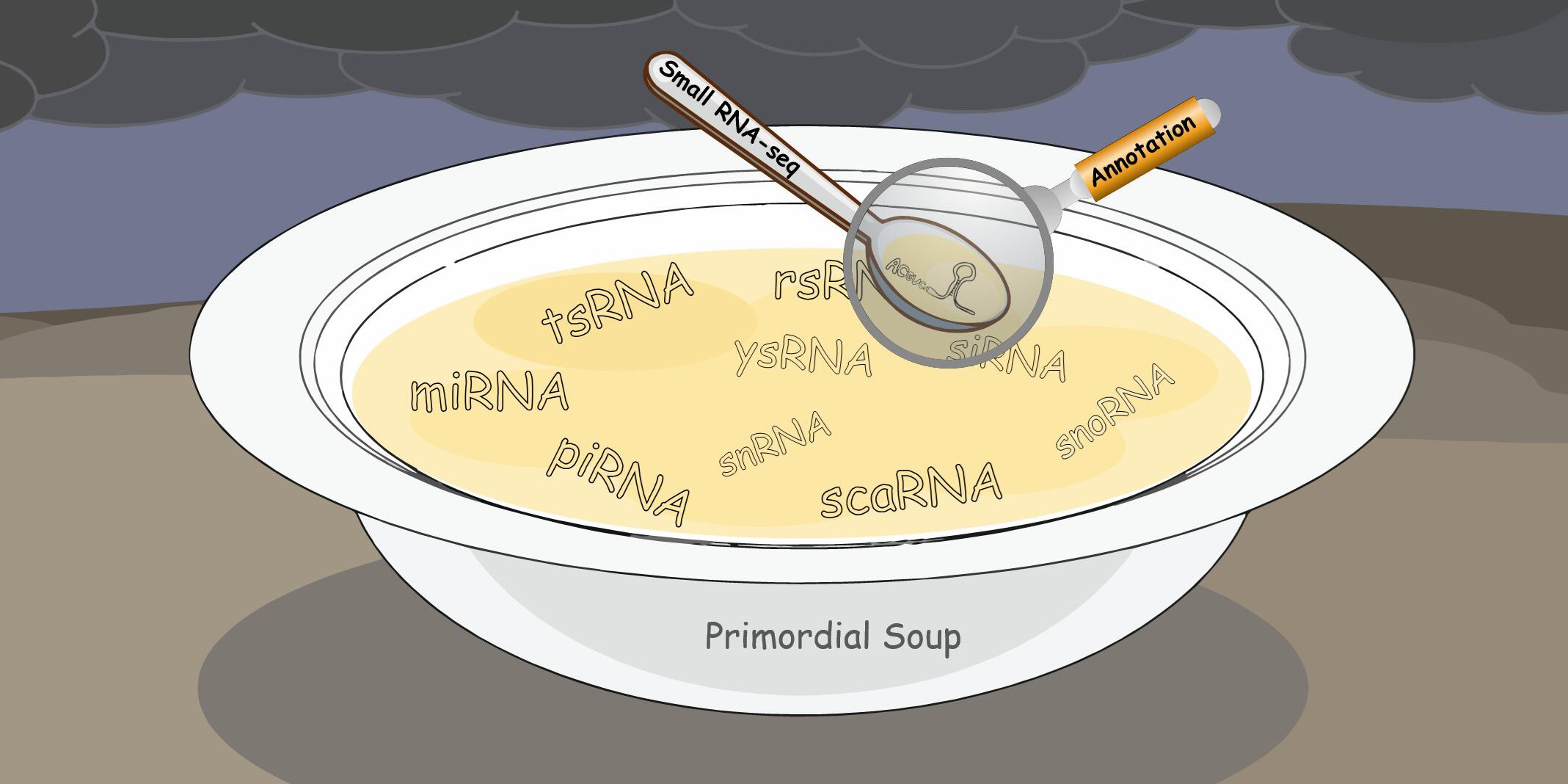

Small RNAs are a widespread group of noncoding RNAs found from bacteria to mammals. While the canonical small RNAs, such as miRNAs and piRNAs have already been extensively investigated from various aspects, research on noncanonical RNAs (e.g., tRNA-derived small RNAs tsRNAs, rRNA-derived small RNAs rsRNAs) remains limited.

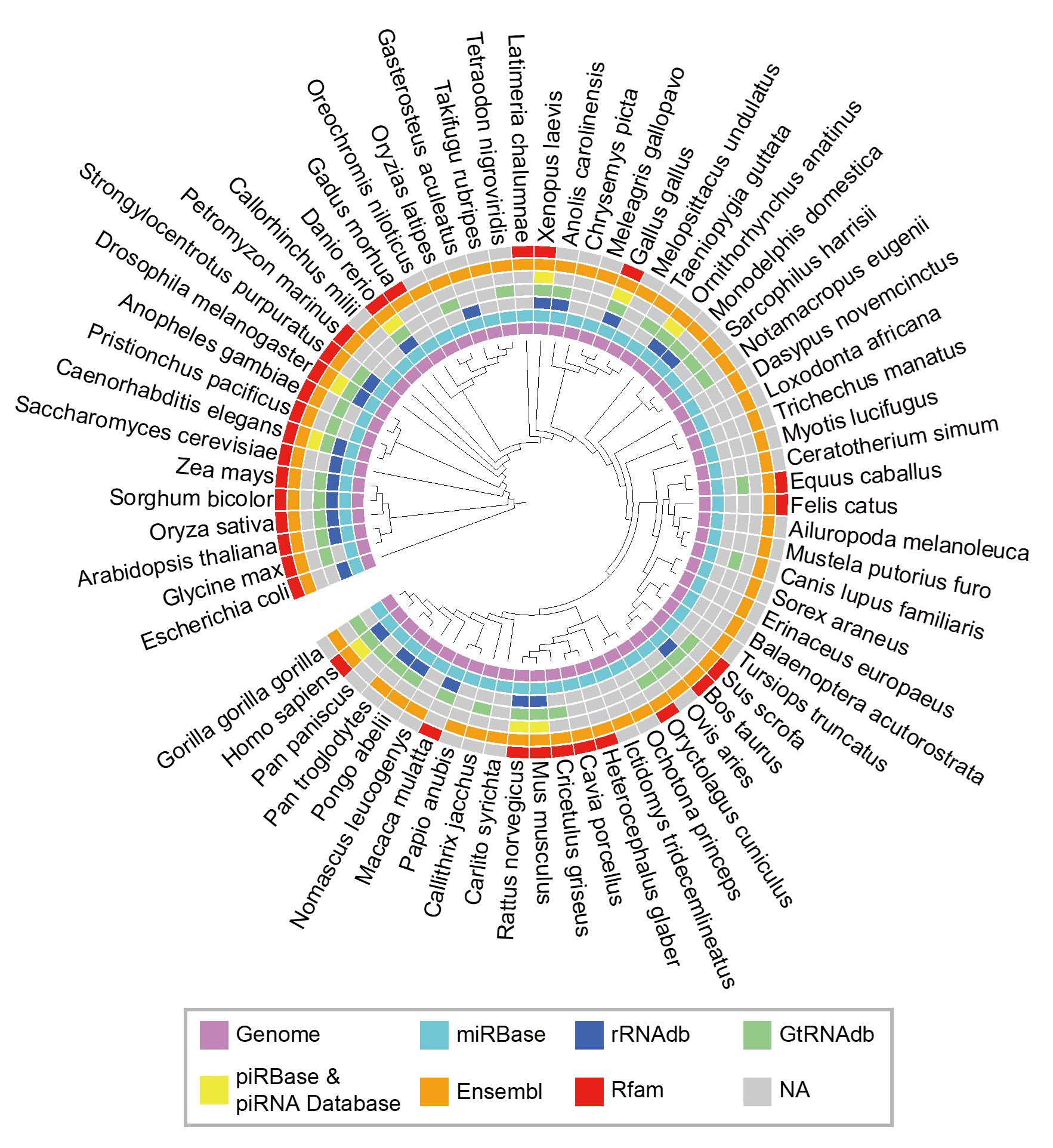

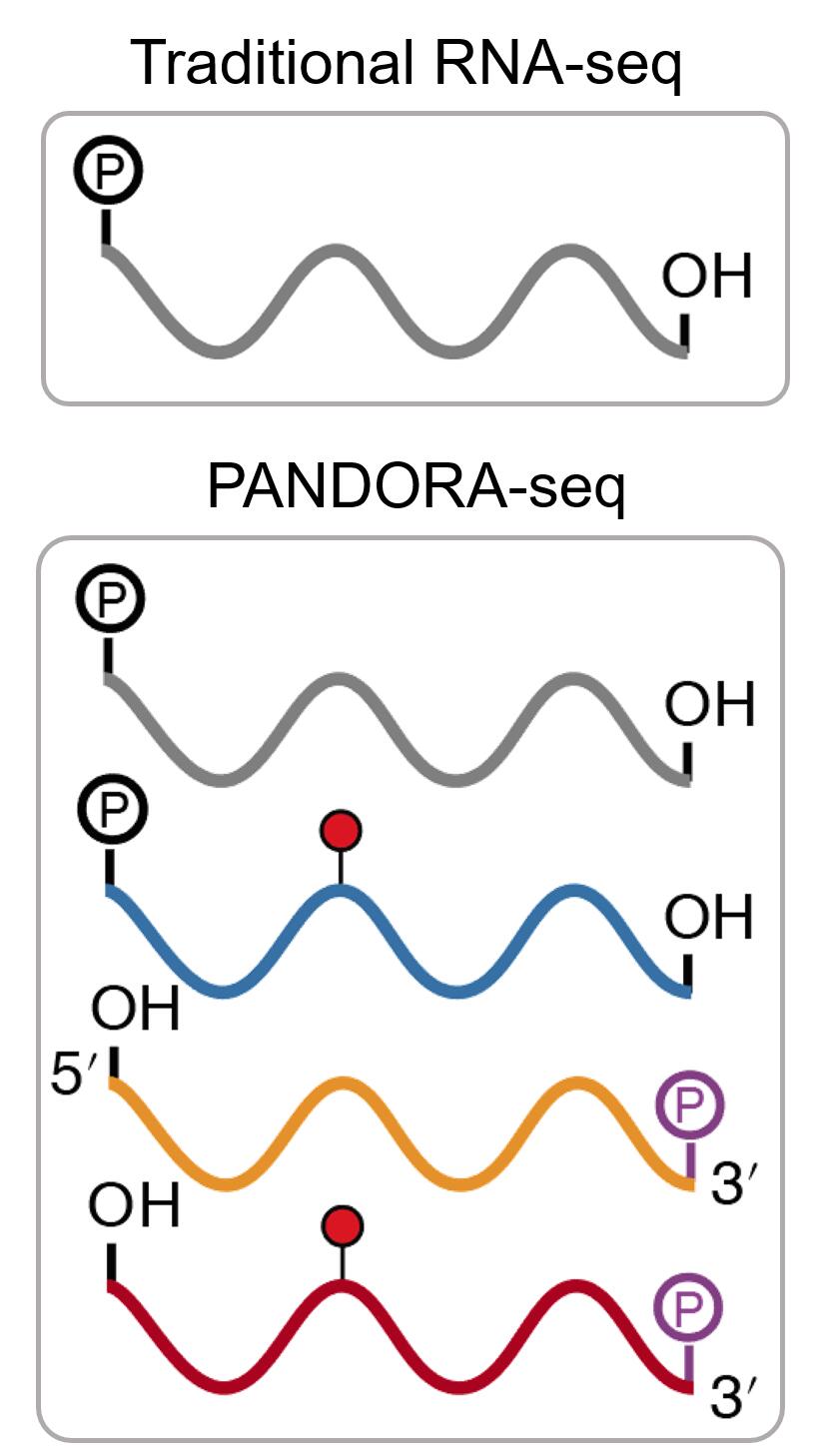

Developing novel small RNA sequencing methods and analysis tools

To explore the expanding universe of small RNAs, we developed a small RNA analysis software called SPORTS. This annotation software has made it easier to study both canonical and noncanonical small RNAs, and has led to the discovery of a TRY-RNA signature for lung disease diagnosis. We also developed a novel small RNA sequencing method called PANDORA-seq to tackle RNA modifications that hinder the detection of small RNAs in traditional RNA-seq. This method uncovered a previously unknown and surprising small RNA landscape dominated by tsRNA/rsRNA rather than miRNA in many tissues and cells.

Discover noncanonical small RNA species and their functions

It has been over 10 years since we made a discovery of a new type of non-canonical small RNA, tsRNA, in the mouse mature sperm. This marked the first time tsRNA’s existence was identified under physiological conditions. The journey continued and we discovered that tsRNAs were not just present in sperm but also in the serum of a wide range of vertebrates and that they were sensitive to pathological conditions. As we delved deeper into their research, we found increasing evidence of acquired traits during paternal exposure being “memorized” in the sperm and inherited by the offspring. This led them to further investigate the role of sperm small RNAs in epigenetic inheritance. We found changes in expression profiles of sperm tsRNAs in mice with a paternal high-fat diet and discovered that the tsRNA/rsRNA-enriched 30-40nt sperm RNA fraction, along with associated RNA modifications, represented a carrier of paternal epigenetic information. We also found that a RNA methyltransferase, Dnmt2, could shape the sperm RNA code and affect the inheritance of traits.

Mammalian embryo symmetry breaking

The July 1, 2005 issue of Science published a list of 125 important questions in science, one of which caught our eyes, tightly: How is asymmetry determined in the embryo?

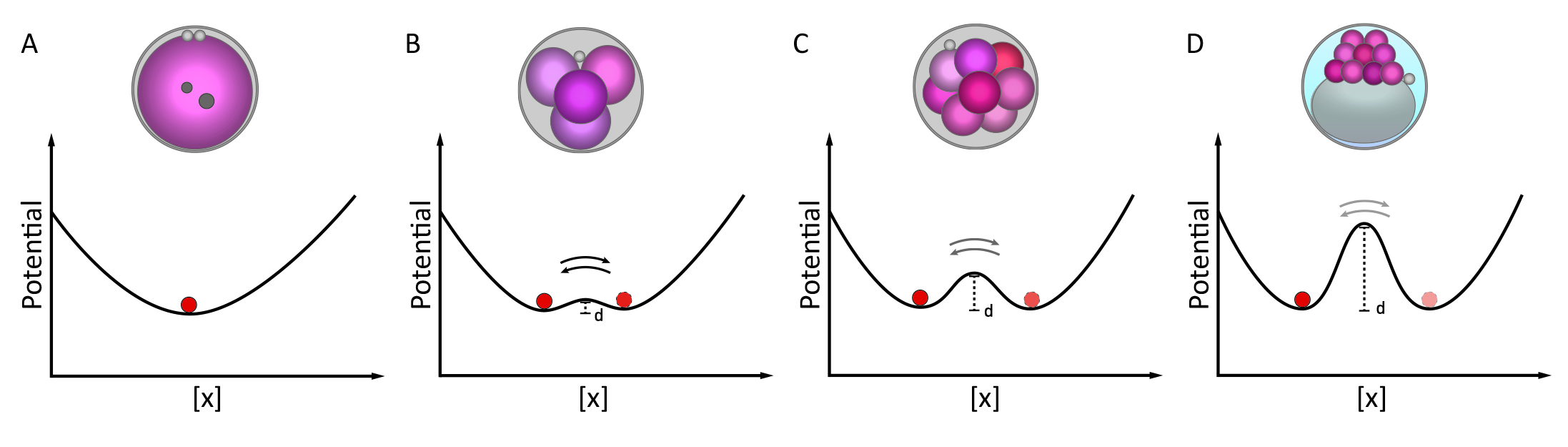

Comparing the embryo development in different species, such as worms, frogs, and sea urchins, with that of mammalian embryos. In the former, the fates of the descendent blastomeres are dictated by asymmetrically deposited morphogens, whereas in the latter, the development of cell fate specification is more subtle and is guided by gradual differences between the blastomeres. This is thought to be due to the lower number of eggs produced by mammals compared to other species, which requires a higher level of resilience to survive early lethality. The developmental plasticity of mammalian embryos is a topic of debate, with some views suggesting that the lack of pre-patterning means blastomeres are not identical, but that differences between them gradually amplify to drive pattern formation while maintaining developmental plasticity.

Searching the driving force of mammalian embryo division and differentiation

The process of cells in mammalian pre-implantation embryos transitioning from a totipotent state to different fates occurs within a limited number of cell divisions. The timing of the emergence of the first blastomere-to-blastomere asymmetry and how it leads to the formation of distinct cell fates are long-standing questions. By using a combination of single-cell RNA sequencing analysis and mathematical modeling, we found that the first asymmetries emerge as early as the first cell division and follow a binomial distribution pattern. The mathematical model suggests that cells have a natural tendency to differentiate. Our findings support the scenario where competing lineage specifiers within an early blastomere determine its fate based on their relative ratio, leading to the formation of a flexible “lineage strength” before morphological differences become apparent. We also highlights the role of the heterogeneously expressed long non-coding RNA, LincGET, in driving the process of symmetry breaking in the 2-cell mouse embryo.